Samantha

He went out the side door that faced the pasture. Coffee in hand he drained and set the chipped cup down onto the oily, sagging table next to the door and stepped into the torn rubber muck boots that he kept meaning to replace. Stretching, he looked as he always did at the mountain that defined his horizon. Still dark in it's somnolence, the sun rising opposite not yet touching it with light.

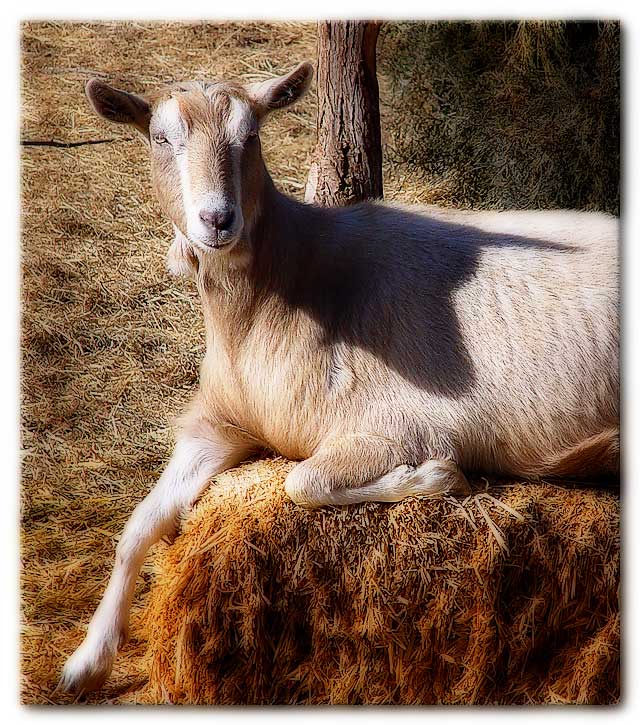

They were waiting at the fence for him as they always did. Some at least. The young. The aggressive. The older and more passive still down, working on the last of the night's cud. Deer-marked, their flat brown and white striped faces and erect ears watched him.

He crossed to the chicken yard that bordered the pasture and closed the gate and strapped it to keep the more creative from bulling their way in and bingeing on chicken feed. Then he went around to the pasture gate and opened it. They lined up in their inscrutable order to leave the pasture and access their morning treat; browsing bits of Cypress bark off the trees to which they were otherwise forbidden access. He greeted each as they came out, feeling a suspect udder here, looking at noses for signs of illness, touching ears to gauge body heat. Giving each a final pat he let them go one at a time. The curious one went right away nose up to the chicken yard gate to see if he had forgotten to strap it shut. Foiled, she joined the others.

Carrying a bale of cedar shavings and a hay fork he first went to the pen of the old crippled one. The others were all her progeny but they would try to kill her now in her weakness and so she stayed protected and alone in her pen. Years before he had stubbornly refused to put her down during an ugly illness and they had bonded and she had recovered and given birth to two healthy twin does. Arthritis now crippled her and he could find no cause for it and worse; no cure. It ate at him. He cursed it's unfairness. The not knowing.

Her ears perked and she motioned to him with her nose, waving him in. He unstrapped the gate and opened it and set the fork and the bale of shavings to one side, out of her way. She struggled to rise and he bent to help her, pulling her weaker left front leg up and out and helping her to her knees. While she kneewalked around in a leftward circle he forked out the old, wet bedding and replaced it with fresh cedar shavings just as she lunged her self into position and groaning in either pain or frustration or both laid herself down in her fresh bed.

He knew she was unhappy. Not free to roam and browse with her offspring, not free to do what she was born to do and yet he could not put her down. Not yet. While the light in her eyes shined for him, while she still perked her ears and tossed her head at him each morning he could not do it. He imagined her taking that last breath and shook his head to rid himself of that awful picture.

He bent to wish her good morning and still panting heavy from the effort of movement she licked his face all over and his hair too. He rubbed her ears and patted her flanks and stroked her neck.

He went out of the pen and strapped the gate shut. The others in their hunger had begun to push and shove each other and argue over bits of leaves or tree bark or other unseen and indecipherable offenses.

He took a leaf rake and swept the previous night's wasted hay up into a pile and forked it into the wheel barrow and hauled it out to the far end of the pasture and dumped it and spread it around. Then he hauled the hose to the water buckets and troughs and filled them with the day's water.

He went out the pasture gate and shut it behind him so none could get back in and went to the hay shed and began to parcel out the morning's feed. Then he carried it back through the pasture gate and again shut it behind him so none could follow.

They grouped at the gate, butting and pushing and some became angry one with another. He stopped inside the gate and waited and they looked at him. He allowed them back in only if their backhairs were down and there was no sign of trouble. Fighters would have to fight outside the pasture and not be allowed to trample the fresh feed. When all were in and calm and eating each in her own place he carried a flake of hay to the old one and entering her pen he broke off a piece of hay and set it before her and put the rest in the back of the pen where she would not spoil it should she decide to move. She looked at him and out at the others and back at him. He told her it was alright and none would take her hay and she buried her nose in the hay and pulled out a great clump and began chewing it. He went out of the pen and out of the pasture and put the clip and the strap on the pasture gate. Then he went to the poultry house and unhooking the eye hooks securing the door let the chickens out. They came out one by one, the old one-eyed rooster first. He counted them and looked them over for any signs of illness or distress. When they were all out he left the poultry yard and walked back to where he could look over the entire scene one more time.

The sun had lit the mountain and crept down to the level of the barn roof. In the morning cool the light on the metal roof had drawn a congregation of flies warming themselves. He thought he should spray them but he did not.

Shucking off his boots outside the door, he went back into the house to feed himself. In desperation a fly buzzed in the leavings at the bottom of his forgotten cup.

In the end it was neurological. During the last few weeks she had spells where she seemed not to know him. Fearful. On his approach to her pen she would scramble up onto her knees and if he appeared to be about to open the pen gate would turn and scramble as if trying to get away. He would let her settle and then try to approach her again and she would once again try to escape. Two, three, four times this would happen while he spoke gently to her and finally she would relax as if she knew him and would take her treats and her water and finally dig into her hay. Then she would have several days happy to see him and waving her nose to him again like always.

On the last night her back legs would not work and she didn't seem to know where she was or who he was. She tried to rise and could not and screamed. In pain no doubt but worse; in abject fear. Wide eyed and head cocked at a disturbing angle. He tried many times to approach her without success and at last tossed hay over the fence to her, let her be and went in to try and sleep. Getting up in the night he watched her from the porch. Her ears cocked to his throat clearing but he could tell that she wasn't quite looking at him. He knew it was to be her last night.

In the morning he took out a pan of her favorite treats; tomatoes and grapes, bread smeared with peanut butter. He approached the pen but she would have none of it, writhing and whipping her head trying to get up and get away. Untrimmed hooves digging her into a hole. He moved around to the side of the pen away from the gate where she knew he could not enter and she calmed. He tossed her treats to her through the fence and she grabbed them and ate as greedily as ever. He spoke to her. He told her he never meant for her to suffer this long and how sorry he was for being so selfish. She looked towards him eyes wide. Spooked. He went and broke a good sized bough off one of the cypress trees and poked it through the fence and she began to chew on it happily. He let her be.

The vet came and they stood outside the fence and he said she's out of it, look at the cant of her head no wonder she's acting scared I bet she's gone at least partially blind. Throwing clots or having strokes, it's probably why her back legs have failed as well.

His wife came to help and they entered her pen and he knelt on one knee and managed to get her head in his hands resting it on his knee. He stroked her neck and spoke to her and she seemed to know who he was and calmed. With her neck exposed the vet was able to find a vein without difficulty for the initial shot that would put her out but not down. He held her and felt the pain and fear flow out of her as she relaxed. Her breathing eased and became shallow. He kissed her nose and told her goodbye and thanked her again.

As the vet sought the vein again, he briefly wondered at the incongruously happy pink color of the solution that would end her life. Barbie Doll pink. Little girl's purse pink. Double-Bubble pink. Then again, what better color for a serum that would bring peace and an end to suffering? She took one last deep sigh and slumped completely against him. Silently as he laid her head to the ground he thanked her again and bid her goodbye. He watched as the light left her eyes.

Later as he cleaned her pen, the others browsed, uninterested. Her eldest daughter, who had begun to limp as well a few years before, pawed a spot in the newly disturbed dirt the backhoe had left and laid down. He thought it was just the cool, damp new earth but still, he wondered.

Good bye Samantha, god bless you.

“No lists of things to be done. The day providential to itself. The hour. There is no later. This is later. All things of grace and beauty such that one holds them to one's heart have a common provenance in pain. Their birth in grief and ashes.” - Cormac McCarthy